Operating Systems

Learn how computers manage programs and interact with hardware!

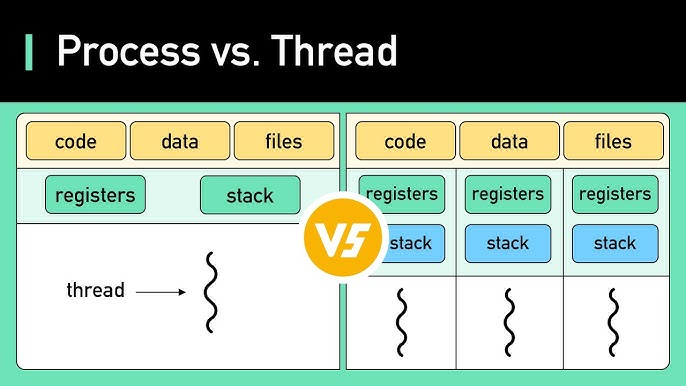

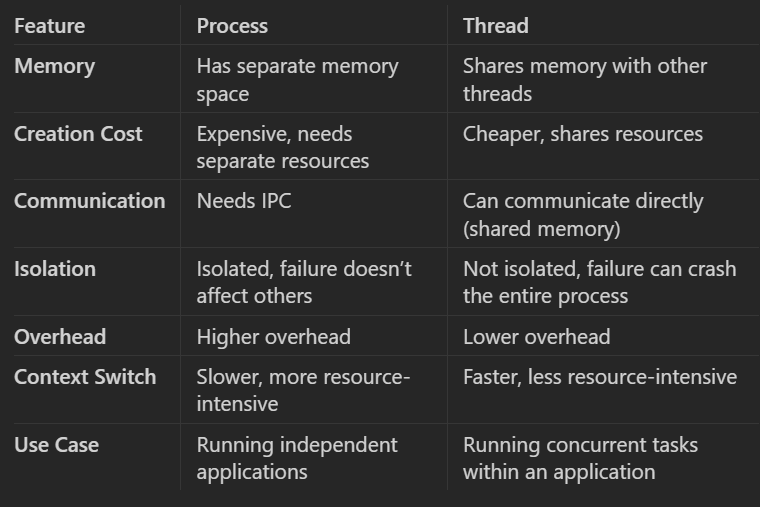

Thread vs Process

| Aspect | Process | Thread |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Independent execution unit with its own memory | Lightweight execution unit inside a process |

| Memory space | Separate address space (isolated) | Shares the same address space with other threads |

| Creation overhead | Heavy (fork/exec) | Very light |

| Context switch time | Expensive (high) | Cheap / fast |

| Resource ownership | Owns resources (memory, file descriptors, etc.) | Shares resources with other threads in process |

| Communication | IPC needed (pipes, sockets, shared memory, etc.) | Direct (shared variables, just need synchronization) |

| Failure impact | Crash usually affects only that process | Crash can kill the entire process |

| Isolation / Protection | Strong (memory protected) | None between threads (can corrupt each other) |

| Parallelism on multi-core | True parallelism possible | True parallelism possible |

| Typical use case | Independent programs, isolation needed | Concurrent tasks within same program (web server, GUI, etc.) |

| Example | Chrome tab, VS Code instance | Threads in a Chrome renderer process |

Race Conditions

Deadlocks

Virtual Memory

Process Scheduling

Inodes

File Descriptors

Soft vs Hard Links

Permissions

Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

Pipes

Queues

Shared Memory

Sockets (Local/Unix vs Network)

Signals

Memory Mapped Files

- What's the difference between a Thread and a Process?

- Key Differences

- What is IPC?

- IPC (Inter-Process Communication) in operating systems refers to a set of mechanisms that allow processes to exchange data and coordinate their actions.

- Process Isolation:

- Processes run in their own address spaces; they do not share memory directly.

- IPC allows processes to bypass this isolation, allowing them to communicate and collaborate.

- Synchronization:

- IPC helps coordinate process execution, ensuring that processes do not interfere with each other or work on shared data simultaneously without proper management (avoiding race conditions).

- Types of Communication:

- Unidirectional (one-way communication, e.g., sending a message) or

- Bidirectional (two-way communication, e.g., exchanging messages).

- What are common methods in IPC?

- Named Pipes (FIFOs):

- Allows unidirectional or bidirectional communication between two related or unrelated processes.

- Processes communicate by writing data to one end of the pipe and reading it from the other end.

- Named pipes exist as special files in the file system, allowing unrelated processes to communicate.

- Unnamed Pipes:

- Typically used between parent-child processes or processes that share a common ancestor.

- They are unidirectional and used only for communication between closely related processes.

- Message Queues:

- A queue of messages stored in the kernel, enabling processes to send and receive messages asynchronously.

- Provides greater flexibility in terms of message priority and retrieval, allowing processes to read messages in order or based on priority.

- Each message in a queue can contain additional metadata like type or priority.

- Shared Memory:

- A block of memory that is shared between two or more processes.

- Fastest form of IPC because processes can read and write directly to memory without involving the kernel after setup.

- Requires proper synchronization (e.g., using semaphores or mutexes) to prevent race conditions or data corruption, as multiple processes can access the same memory simultaneously.

- Semaphores:

- Used for synchronization between processes or threads, rather than direct data exchange.

- Can be thought of as counters that are used to control access to shared resources.

- Semaphores help prevent race conditions by ensuring that only a specific number of processes can access a resource at a time.

- Sockets:

- A communication mechanism primarily used for communication between processes over a network.

- Allows processes on different machines (or the same machine) to communicate using network protocols like TCP or UDP.

- Provides flexibility in terms of local and remote process communication, and is the foundation of client-server communication models.

- Signals:

- Signals are asynchronous notifications sent by the OS to a process, usually to indicate that a particular event has occurred (e.g.,

SIGKILLfor termination,SIGINTfor interrupt). - Signals are not used for data transfer, but for control and notification.

- A process can define signal handlers to specify what actions to take when a signal is received.

- Signals are asynchronous notifications sent by the OS to a process, usually to indicate that a particular event has occurred (e.g.,

- Memory-Mapped Files:

- A mechanism that maps a file or a portion of it into the process’s address space.

- Allows multiple processes to share access to a file by mapping it to their address space, thus enabling them to share data via the file system.

- RPC (Remote Procedure Call):

- Allows a process to execute a procedure (function) in another process, which can be on the same machine or a different one (remote).

- Provides abstraction where communication is handled like a function call rather than explicit message passing.

- Named Pipes (FIFOs):

- How do you prevent deadlocks?

- Deadlock conditions:

- a) Mutual Exclusion:

- Eliminate mutual exclusion where possible by allowing resources to be shared (non-exclusive). For example, read-only access to files can be granted to multiple processes.

-

b) Hold and Wait:

- Avoid holding resources while waiting for others by ensuring that processes request all necessary resources at once. This prevents holding one resource while waiting for another.

- For instance, requiring processes to request all their resources at the start (or releasing held resources before requesting new ones).

-

c) No Preemption:

- Allow preemption of resources by forcibly taking a resource from a process when needed by another. For example, if a process holding a resource is blocked, its resource can be preempted and given to another process.

- Preemption works well in memory and CPU scheduling but can be difficult for more complex resources like files or devices.

-

d) Circular Wait:

- Impose an ordering on resource requests. This ensures that resources are always requested in a specific, global order, which prevents circular waiting. For example, if processes must always request resources in order (R1, R2, R3), circular waiting cannot occur.

- a) Mutual Exclusion:

- Deadlock avoidance

- Banker's Algorithm

- Resource Allocation Graphs

- Two-phase locking (DB)

- Ordered locking

- Deadlock recovery

- Preempting Resources: The system forcibly takes resources from some processes (rolling them back) to allow others to proceed.

- Killing Processes: The system can terminate one or more processes involved in the deadlock, thereby releasing the resources they hold. This can be done:

- Abruptly (without allowing the process to finish).

- Gracefully (allowing the process to save its state or clean up).

- Process Rollback: If processes have been checkpointed, the system can roll back processes to an earlier safe state before the deadlock occurred.

- Deadlock conditions:

- What is Banker's algorithm?

- Algorithm that checks whether allocating resources to a process will leave the system in a safe state

- Tell me about race conditions and what are some methods to mitigate them.

- Locks (Mutual Exclusion)

- Locks are the most common method to prevent race conditions. A lock ensures that only one thread can access a critical section (shared resource) at a time.

- Mutex (short for mutual exclusion) is a common type of lock used to prevent multiple threads from executing the same code simultaneously.

- Spinlocks are lightweight locks that repeatedly check if a lock is available without sleeping, useful for short critical sections.

- Semaphores

- A semaphore is a synchronization primitive that controls access to shared resources. It allows more flexibility than a mutex because it can permit more than one thread/process to access the resource, up to a specified limit.

- Binary semaphore acts similarly to a mutex (allowing only one thread access).

- Counting semaphore allows a specified number of threads to access a resource concurrently.

- Atomic Operations

- Atomic operations ensure that certain operations on shared data (such as incrementing or decrementing) are performed as a single, indivisible step. This prevents other threads from interrupting the operation and eliminates race conditions in simple cases.

- Atomic variables (e.g.,

std::atomicin C++) ensure that operations like increment, decrement, or compare-and-swap are thread-safe without needing explicit locking mechanisms.

- Message Passing

- In concurrent systems, instead of sharing memory between threads (which can lead to race conditions), message passing can be used. Threads communicate by sending messages to each other, avoiding shared memory access.

- Locks (Mutual Exclusion)

- What is swap space?

-

Key Concepts of Swap Space:

- Virtual Memory Extension:

- Swap space is used to extend the system's virtual memory. Virtual memory allows the system to run more applications than would fit into physical RAM by "swapping" out inactive portions of memory to disk when the RAM is full.

- Paging:

- When the system runs out of physical RAM, the OS will move portions of memory that are not currently in use (e.g., inactive processes or background applications) from RAM to swap space. This process is called paging.

- When those portions of memory are needed again, the system will swap them back into RAM, possibly swapping other data out to make room.

- Swapping:

- Swapping refers to the complete movement of entire processes between RAM and swap space. Although rarely used in modern systems, swapping can occur in some extreme cases when memory is severely constrained.

- Performance Impact:

- Since reading from and writing to swap space (on disk) is significantly slower than accessing data in RAM, using swap space can lead to performance degradation, especially if the system heavily relies on it (this is known as "thrashing").

- Swap space is a safety net for low-memory situations, but it is not a substitute for physical RAM in terms of performance.

- Usage Scenarios:

- Swap space is especially useful when the system is running multiple applications that together exceed the available RAM.

- It allows the system to temporarily store inactive parts of programs or data, freeing up physical memory for more active tasks.

- In systems that hibernate, swap space may also be used to save the entire system's memory contents to disk when the system is suspended.

- Types of Swap Space:

- Swap Partition: A dedicated partition on the disk that is reserved for swapping.

- Swap File: A regular file on the filesystem that can be used as swap space, which can be easier to resize or create on the fly compared to a swap partition.

- Virtual Memory Extension:

-

How Much Swap Space Should Be Allocated?

The amount of swap space required depends on several factors:- System RAM: Systems with less RAM benefit more from larger swap space.

- System Usage: Heavy multitasking, memory-intensive applications (e.g., databases, virtualization), or hibernation will require more swap space.

- A general rule of thumb is to allocate 1 to 2 times the amount of RAM, but modern systems with lots of RAM often use much less swap.

-

- Do you know how does memory management work in OS?

- Key Concepts in OS Memory Management

1. Memory Hierarchy

- Registers and Cache: Fast, small memory inside the CPU (registers) and close to the CPU (cache) used for high-speed operations.

- Main Memory (RAM): Directly accessible by the CPU but slower than cache. Holds data and instructions currently in use.

- Secondary Storage (Disk): Non-volatile storage (like HDDs or SSDs) used for data that is not immediately needed. Virtual memory uses this storage as an extension of RAM.

2. Address Spaces

- Physical Address Space: The actual addresses in the computer’s RAM.

- Virtual Address Space: An abstraction provided by the OS where each process has its own private address space. Virtual memory allows programs to use more memory than the physical RAM by paging parts of the address space to disk.

3. Memory Allocation

- Static Allocation: Memory is allocated at compile time. Variables have a fixed size and location in memory.

- Dynamic Allocation: Memory is allocated at runtime using functions like

mallocin C ornewin C++. The OS is responsible for finding free memory and assigning it to the requesting process.

- Memory Management Techniques

a) Contiguous Memory Allocation

- In this scheme, each process is given a single, contiguous block of memory. Simple but inefficient due to issues like fragmentation:

- External Fragmentation: Small gaps appear between allocated memory blocks, making it difficult to allocate large contiguous blocks.

- Internal Fragmentation: Memory allocated to a process is slightly larger than needed, leaving unused space inside the block.

b) Paging

- Paging divides both the virtual and physical memory into fixed-size blocks called pages (for virtual memory) and frames (for physical memory). The OS maintains a page table to map pages to frames.

- Advantages:

- Eliminates external fragmentation.

- Allows non-contiguous allocation of memory, increasing flexibility and efficiency.

- When a process needs a page not currently in RAM, a page fault occurs, and the OS retrieves the page from disk (swap space) and places it in RAM.

Paging Example:- A process might request memory, and the OS divides it into multiple pages (say 4 KB each). These pages can be loaded into different locations in physical memory (frames). The page table tracks where each page is located.

c) Segmentation

- Segmentation divides memory into different variable-sized segments, each corresponding to a logical unit of the program (e.g., code, data, stack). Each segment has its own segment number and offset.

- Segmentation is more aligned with how programs view memory (e.g., different segments for code, data, heap, stack).

- Drawback: External fragmentation can still occur as segments are of varying sizes and require contiguous memory.

d) Virtual Memory

- Virtual memory allows processes to use more memory than what is physically available on the system by using a combination of RAM and swap space on disk. Virtual memory creates the illusion that each process has its own large, contiguous block of memory.

- When the physical memory is full, inactive pages from RAM are moved to swap space (on disk), freeing up space for active pages. The OS handles moving pages between RAM and disk using paging.

- Benefits:

- Allows for multitasking and larger programs.

- Separates physical memory management from the process, providing an abstraction.

Virtual Memory Example: - Suppose a system has 8 GB of RAM but a process requires 10 GB of memory. The OS uses 8 GB of physical memory and "swaps" the other 2 GB to the disk, allowing the process to continue running.

e) Memory Protection

- The OS enforces memory protection to ensure that processes do not interfere with each other’s memory space.

- Each process has its own address space, and the OS ensures that no process can access the memory of another process unless specifically allowed.

- Memory protection is achieved using mechanisms like:

- Base and Limit Registers: These registers define the start (base) and the size (limit) of a process's memory. Any access outside this range is flagged by the OS as a violation.

- Paging and Segmentation: The OS ensures that processes only access the pages or segments allocated to them.

- In this scheme, each process is given a single, contiguous block of memory. Simple but inefficient due to issues like fragmentation:

- Page Replacement Algorithms

When the system runs out of free pages, the OS must select a page to replace (i.e., move from RAM to disk). This selection is done using page replacement algorithms:- FIFO (First-In-First-Out): Pages are replaced in the order they were loaded into memory.

- LRU (Least Recently Used): The OS replaces the page that has not been used for the longest time, based on the assumption that recently used pages are more likely to be used again.

- Optimal Algorithm: Replaces the page that will not be used for the longest period in the future (though it's difficult to implement as it requires knowing future page accesses).

- Clock (Second-Chance): A circular list of pages is maintained. When a page needs to be replaced, the OS checks if the page has been used recently (via a "reference bit"). If the bit is set, the OS gives it a second chance and moves to the next page.

- Key Concepts in OS Memory Management

- Do you know about inodes?

- Do you know about file descriptors/handlers?

- Soft links vs hard links?

- Process scheduling?